Contents

Methods of Tax Audit: A Comprehensive Guide

Tax audits are a fundamental part of any nation’s tax administration system. They serve as a mechanism for tax authorities to ensure that individuals and businesses are accurately reporting their income, deductions, and other tax-related information. By conducting audits, authorities can detect errors, prevent tax evasion, and promote a culture of voluntary compliance. However, tax audits are not a one-size-fits-all process. Depending on the circumstances, different methods and techniques are employed to achieve the objectives of the audit. This article explores the principal methods of tax audit, the procedures involved, and how technology is transforming the audit landscape.

1. Types of Tax Audit Methods

Tax authorities employ various approaches to auditing, each tailored to the complexity of the taxpayer’s affairs, the nature of the business, and the specific issues at hand. The three primary methods are:

a. Correspondence (Mail) Audit

A correspondence audit is the simplest and least intrusive form of tax audit. It is conducted entirely by mail. The tax authority sends a letter requesting clarification or additional documentation regarding specific items on a tax return—such as proof of deductions, income sources, or credits claimed. The taxpayer responds by mailing the requested documents, such as receipts, bank statements, or invoices.

When is it used?

Correspondence audits are typically used for straightforward issues or minor discrepancies that do not warrant an in-person meeting. They are common for individual taxpayers and small businesses.

b. Office Audit

An office audit is more comprehensive than a correspondence audit. The taxpayer is required to visit a tax authority office, bringing relevant records and documents. During the meeting, an auditor reviews the information, asks questions, and may request further clarification on specific items in the tax return.

When is it used?

Office audits are usually reserved for cases where multiple issues need to be examined, or where the amounts involved are larger. They are common for both individuals and small to medium-sized businesses.

c. Field Audit

A field audit is the most extensive and detailed type of audit. In a field audit, the auditor visits the taxpayer’s home, business premises, or accountant’s office. This allows for a thorough examination of original records, observation of business operations, and direct interviews with staff or management.

When is it used?

Field audits are typically conducted for complex cases, large businesses, or when significant discrepancies or potential fraud are suspected. They allow auditors to assess the taxpayer’s operations in real time and gather evidence that may not be available through documents alone.

2. How Are Taxpayers Selected for Audit?

Tax authorities use several methods to select which tax returns to audit:

-

Random Selection and Computer Screening: Many audits are chosen through statistical algorithms or computer models that flag returns with unusual patterns or outliers compared to similar taxpayers. This helps identify cases that may warrant closer scrutiny.

-

Related Examinations: If a taxpayer is involved in transactions with another party whose return is under audit (such as a business partner or supplier), their return may also be selected for review.

-

Targeted Audits: Some audits are triggered by specific information, such as tips from whistleblowers, third-party reports, or evidence of non-compliance.

-

Routine or Scheduled Audits: Large corporations or certain industries may be subject to regular audits as part of ongoing compliance programs.

3. Standard Audit Procedures and Techniques

Regardless of the audit method, tax auditors follow standardized procedures to gather and evaluate evidence. These procedures are designed to ensure a fair, thorough, and systematic review of the taxpayer’s affairs.

| Audit Procedure | Description |

|---|---|

| Document Examination | Reviewing financial statements, invoices, contracts, ledgers, and receipts to verify transactions. |

| Observation | Observing business processes or inventory counts to confirm compliance with reported activities. |

| Inquiry | Asking questions of the taxpayer or employees to clarify specific transactions or practices. |

| Confirmation | Verifying information with third parties, such as banks, customers, or suppliers. |

| Recalculation | Checking the mathematical accuracy of figures in tax returns and supporting documents. |

| Reperformance | Repeating procedures or calculations to confirm the taxpayer’s methods and results. |

| Analytical Procedures | Comparing financial data over time or against industry benchmarks to identify inconsistencies. |

These techniques help auditors form an objective opinion about the accuracy and completeness of the taxpayer’s filings.

4. Industry-Specific Audit Techniques

Tax authorities often use Audit Techniques Guides (ATGs) tailored to different industries. These guides help auditors understand unique business practices, accounting methods, and common risk areas within specific sectors—such as construction, retail, or healthcare. ATGs provide checklists, interview questions, and red flags that auditors should look for, ensuring a more effective and informed audit process.

5. Computer-Assisted Audit Techniques (CAATs)

With the increasing digitization of business records, auditors now rely heavily on computer-assisted audit techniques (CAATs). These methods leverage technology to analyze large volumes of data quickly and accurately. Common CAATs include:

-

Statistical Sampling: Selecting a representative sample of transactions for detailed review, allowing auditors to draw conclusions about the entire dataset.

-

Data Analytics: Using specialized software to identify trends, anomalies, or outliers in financial data.

-

Electronic Verification: Cross-checking electronic records with third-party data sources, such as banks or government agencies.

-

Focused Detail Audit: Targeting specific transactions, accounts, or periods for intensive examination based on initial findings.

CAATs enhance audit efficiency and accuracy, especially for large or complex organizations.

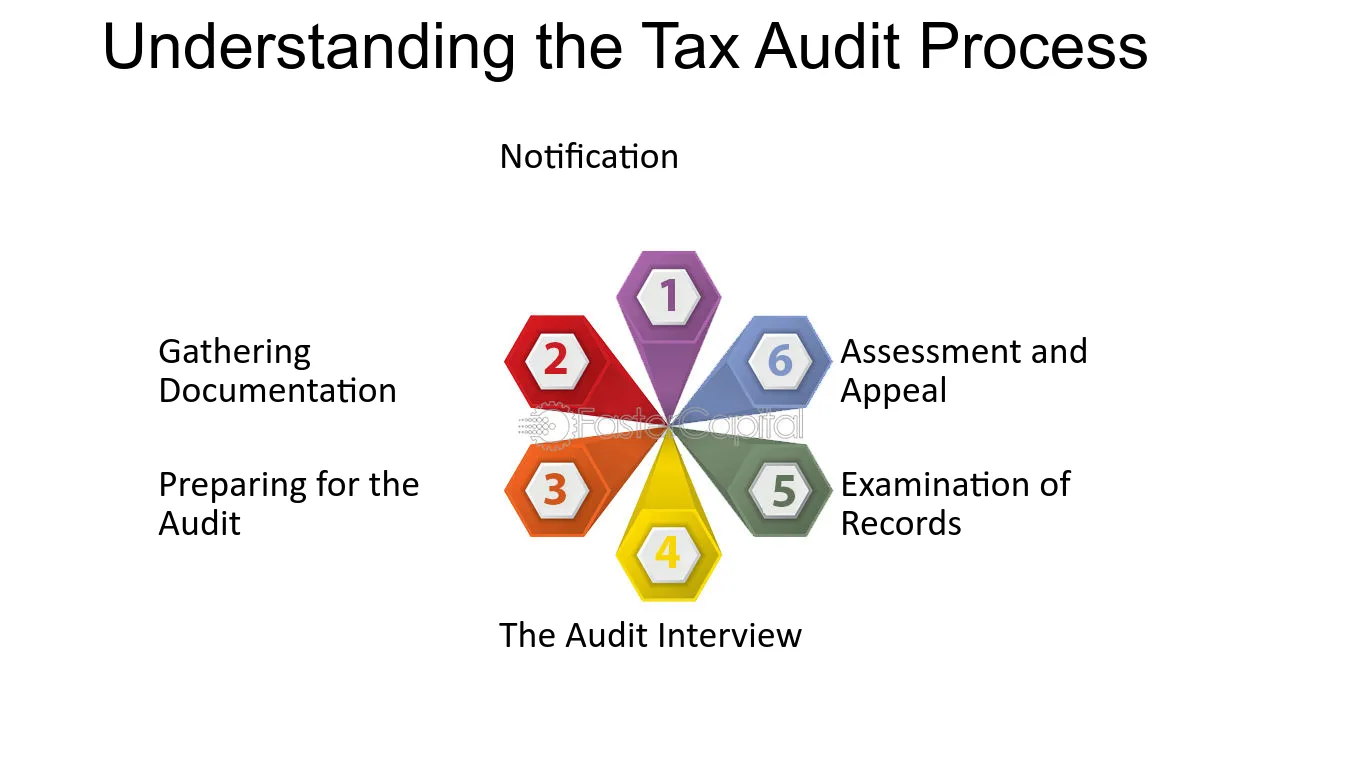

6. The Tax Audit Process: Step-by-Step

A typical tax audit follows a structured sequence:

-

Pre-Audit Planning: The auditor reviews available information and identifies potential risks or areas of focus.

-

Notification: The taxpayer receives a written notice about the audit, usually with a request for specific documents.

-

Initial Interview: The auditor meets with the taxpayer to explain the audit process and gather preliminary information.

-

Examination of Records: The auditor reviews and tests financial records, using the methods described above.

-

Follow-Up Requests: Additional information may be requested if discrepancies or questions arise.

-

Documentation: The auditor keeps detailed notes of findings, interviews, and evidence.

-

Final Meeting: The auditor presents findings and discusses any proposed adjustments with the taxpayer.

-

Resolution: If the taxpayer agrees, adjustments are made and payment arrangements are set. If not, the taxpayer can appeal.

-

Closure and Feedback: The audit is formally closed, and feedback is provided to improve future processes.

7. Emerging Trends in Tax Audit Methods

As technology evolves, so do tax audit methods. Artificial intelligence, machine learning, and big data analytics are increasingly used to detect patterns of non-compliance and automate routine audit tasks. These advancements enable tax authorities to focus resources on high-risk cases and improve audit outcomes.

Conclusion

Tax audits are conducted using a variety of methods, from simple correspondence audits to complex field investigations supported by advanced technology. The choice of method depends on the taxpayer’s profile, the complexity of the case, and the issues at hand. By combining traditional audit techniques with modern data analysis tools, tax authorities can ensure that audits are thorough, fair, and effective in promoting compliance and protecting public revenues. For taxpayers, understanding these methods is key to being prepared and maintaining accurate, transparent records.